Friday, December 12, 2008

A very short introduction to New Criticism

Thursday, December 11, 2008

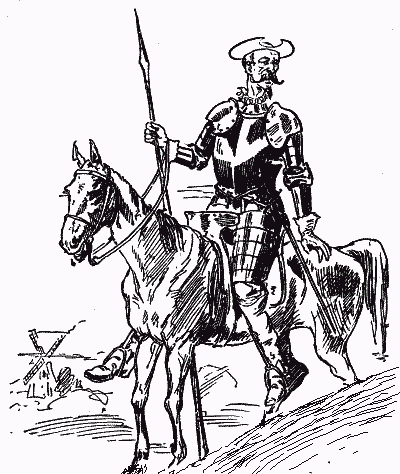

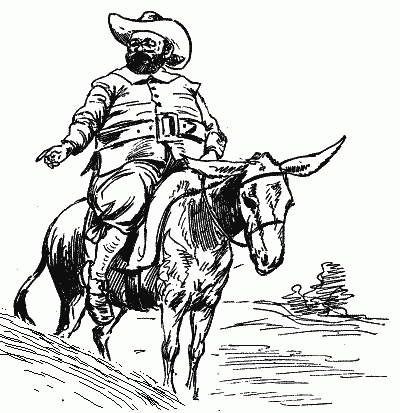

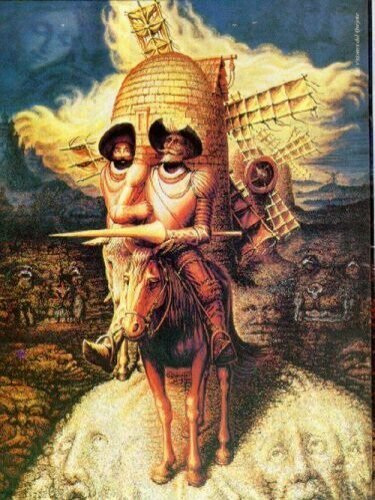

The Depth of Don Quixote: Two Portraits

his under-fed body, he looks like a tradgedy. His armor is worn and moldy, his horse is less than valiant looking.

his under-fed body, he looks like a tradgedy. His armor is worn and moldy, his horse is less than valiant looking.But his behavior works in complete opposition to pathetic appearance.

and respectful, and carries himself with utmost confidence. Nabokov spells it out and I agree; Don Quixote is "a hero in the truest sense of the word" (Nabokov 16).

"How is it possible for you to have accompanied me all this time without coming to perceive that all the things that have to do with knight-errantry appear to be mad, foolish, and fantastic... Not that they are so in reality: it is simply that there are always a lot of enchanters going about among us, changing things and giving them a deceitful appearance, directing them as suits their fancy, depending upon whether they wish to favor or destroy us". (I wonder if Sancho even understands this nobel speech!) And actually now, re-reading that statement as i write it down, i feel tears brimming in my eyes because that is Don Quixote's world, and really it is our world too. That is the tragic sense of life. That there is always evil and people inspired by evil that are working to bring us down. "Enchanters among us" with deceitful intentions. I thought the tragedy of Don Quixote arose at the end of the novel when he renounces knight errantry, but it actually comes into play from the minute he commits himself to it. Sancho is there for comedic relief. But Don Quixote is alone in his world and troubled by his perceptions of the world around him which he sees as his duty to defend. It is outrageously honorable for him to accept this task in the first place, the task of weighing reality and illusion and defending madness and himself against the immoral attacks of the evil he encounters. And Don Quixote is a literary hero for attempting it, but in the end, even he cannot complete it. That is the great tragedy of this novel.

Real Life And Fiction

Thursday, November 27, 2008

At The End of Don Quixote: the book and the man

Even with an awareness of what was revealed in our class discussions about the end of Don Quixote, I still couldn't imagine our knight renouncing his life's quest. Even through the chapter where he is defeated by the knight of the white moon, i still didn't expect Don Quixote to submit to his orders and return to his village. Not very Quixotic! But I knew, on page 893, that our hero was lost, at this moment: "You sound very philisophical, Sancho... and you speak very wisely". What?!!? Did he just call Sancho Panza wise? That's when I knew that my hero was lost, and oh what a loss! Starting in chapter 66, just after his encounter with the knight of the white moon, this novel plummeted from hightly comedic to utterly tragic... all in the span of a few chapters, until his death. Even despite our revealing class discussions I did not expect Don Quixote to really renounce kniight errantry or to die, but its true, the end result is both. In chapter 66 there is still hope, because when he speaks of going into seclusion- his year sabatical from knight errantry- he says to Sancho "in that seclusion we shall sgather new strength to return to the practice of arms, which will never be forgotten by me" (894). But by the last chapter he has worsened to the point of cursing the "practice of arms" forever ("now all the profane histories of knight errantry have become hateful to me... I despise them) and, most tragic to me, saying they were a waste of his life. That is a painful statement. Almost 900 pages of thrill, adventure, passion- all a waste? That, to me, was the most tragic part of our hero's demise. When he says (p. 935) "My judgement is restored, free and clear of the dark shadows of ignorance imposed on it by my grievous and constant reading of detestable books of chivalry. I now recognize their absurdities and deceptions, and my sole regret is that this realization has come so late it does not leave me time to compensate by reading other books that can be a light to the soul". Other books? Is this my same Don Quixote? No it's not. He has lost his honor and self-dignity. No longer the "knight errant, daring and brave", he has transformed into an "ordinary gentleman" (NOOOO!) lacking the confidence, lacking those dignified self-introductions I loved so much! He actually asks Sancho to respond for him, doubting his own judgment and competency. The end of Don Quixote had me in tears, for the loss of a hero. I feel as disenchanted as Dulcinea, whom he sought throughout the entire book to no end.

Even with an awareness of what was revealed in our class discussions about the end of Don Quixote, I still couldn't imagine our knight renouncing his life's quest. Even through the chapter where he is defeated by the knight of the white moon, i still didn't expect Don Quixote to submit to his orders and return to his village. Not very Quixotic! But I knew, on page 893, that our hero was lost, at this moment: "You sound very philisophical, Sancho... and you speak very wisely". What?!!? Did he just call Sancho Panza wise? That's when I knew that my hero was lost, and oh what a loss! Starting in chapter 66, just after his encounter with the knight of the white moon, this novel plummeted from hightly comedic to utterly tragic... all in the span of a few chapters, until his death. Even despite our revealing class discussions I did not expect Don Quixote to really renounce kniight errantry or to die, but its true, the end result is both. In chapter 66 there is still hope, because when he speaks of going into seclusion- his year sabatical from knight errantry- he says to Sancho "in that seclusion we shall sgather new strength to return to the practice of arms, which will never be forgotten by me" (894). But by the last chapter he has worsened to the point of cursing the "practice of arms" forever ("now all the profane histories of knight errantry have become hateful to me... I despise them) and, most tragic to me, saying they were a waste of his life. That is a painful statement. Almost 900 pages of thrill, adventure, passion- all a waste? That, to me, was the most tragic part of our hero's demise. When he says (p. 935) "My judgement is restored, free and clear of the dark shadows of ignorance imposed on it by my grievous and constant reading of detestable books of chivalry. I now recognize their absurdities and deceptions, and my sole regret is that this realization has come so late it does not leave me time to compensate by reading other books that can be a light to the soul". Other books? Is this my same Don Quixote? No it's not. He has lost his honor and self-dignity. No longer the "knight errant, daring and brave", he has transformed into an "ordinary gentleman" (NOOOO!) lacking the confidence, lacking those dignified self-introductions I loved so much! He actually asks Sancho to respond for him, doubting his own judgment and competency. The end of Don Quixote had me in tears, for the loss of a hero. I feel as disenchanted as Dulcinea, whom he sought throughout the entire book to no end.In Memory of WB Yeats

http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/15544

More term paper support via Don Quijote

Term paper posted

"This purifying of wit-this enriching of memory, enabling of judgment, and enlarging of conceit-which commonly called learning, under what name soever it come forth, or to what immediate end soever it be directed, the final end is to lead and draw us to as high a perfection as our degenerate souls, made worse by their clayey lodging, can be capable of."

Sir Philip Sidney

To Inform. To take. To create. By means of my education I have come and will continue to come into my own. Learning has led me to an awareness of my own passion for poetry, and thus, passion for life: of what I need and where I need to go in my life. This quote from Sir Phillip Sidney’s “Defense of Poetry” succeeds in expressing expresses in words what, naturally, I could not, and so stood out from the entire essay to me, and this entire course, as a summary of what I’ve been mulling over in my mind for so long: the beauty of knowledge, education, information: the poetry of wisdom. It is through this journey of learning that I have and will continue to confront the best version of myself.

I would like to model that ideal version of myself on that ingenious hidalgo Don Quixote of La Mancha, a hero by my standards, and in a sense that is completely un-pared in all literature I’ve encountered. Senor Quixote begins his quest when he dedicates himself to the pursuits of knight errantry; he makes it his mission to imitate the language of his books. It takes an understanding and appreciation of literature (which I harbor in my heart as an English major) to consider this mission as one of utmost honor, and not in the least bit farce. In fact I envy our hero for boasting this as his life’s mission: to live himself into his books. Don Quixote speaks of himself and his adventures in the style of the books of chivalry that have ransacked his mind. Oh, that Don Quixote would ransack my mind and invoke me to speak in this high rhetoric so long ago lost! Even if everyone I encounter on my journey thinks me mad, that I would pay it no mind, like our hero. I have wistful notions of adopting Don Quixote’s mission and his rhetoric, but alas, I cannot even read his words out-loud and sound convincing, much less invent my own discourse. I suppose I fear those accusations of madness that the Knight of La Mancha handles so gracefully. That I would be so graceful, this Knight is my hero! The high-rhetoric and wit and wisdom via madness that Don Quixote possesses, his delightfully dignified manner of presenting himself: I envy the hidalgo for all these heroic qualities.

As different as I am from Don Quixote in some respects (those listed in the previous sentence, for instance), I feel smugly similar to him in others. We both have our books, of course (that is we share a dependence on literature). And we have something else, too.

I recall one of many episodes where the knight defends himself and his profession, in Chapter 13 of the First Part, after Don Quixote has met a group of goatherds on the road and is traveling with them to a funeral. One of the travelers they encounter en route to the burial begins to interrogate Don Quixote about his purpose in the land, to which he reiterates his usual elegant explanation of his mission as a knight errant. They immediately consider him mad, both for his exuberant undertaking and equally exuberant way of relating it. They continue to inquire, so as to gauge exactly how mad he is. Don Quixote speaks to them of great knights and soldiers of the past like King Arthur, and then audaciously praises theses knights as more valiant than priests and religious men, because they actively defend the morality that priests only speak about. “In this way we are ministers of God on earth, the arms by which His justice is put into effect on earth” (Cervantes 88). It’s an outrageous claim, I know, but I would defend the poets in the exact same way, including myself: the poets represent the divine in art. Further on in the book, Don Quixote gets another chance to explain lend his knightly wisdom and opinions to a stranger he meets on the road- this time a man in a green coat, with a son studying languages in university. The man in the green coat confesses that he is troubled by his son’s coursework, which he hardly considers to be an “area of knowledge” worth studying. Don Quixote does a better job than I can of defending his son’s choice of curriculum, as well as defining anagogy and praising the poet, explaining that the natural poet, “with that inclination granted to him by heaven, with no further study or artifice composes things that prove the truthfulness of the man who said: Est Dues in nobis” (Cervantes 557). God is in us.

Outrageous. Extravagant. Over-the-top. How could I compare myself to that ingenious knight of La Mancha? I suppose I aim to model myself off of this man just as he does those warriors in his beloved books of chivalry. And since the imaginative Don Quixote makes a far better symbol of poetry than he does a knight errant anyway, maybe it’s not that outrageous.

And so I declare that I am an English major, “the kind, as people say, who go to seek adventures” (Cervantes 553), and like my hero, I am willing to leave my home and comfort and “throw myself into the arms of Fortune so that she may carry me wherever she chooses” that I might “fulfill a good part of my desire” (Cervantes 553). While our desires may differ- his being “to revive a long-dead knight errantry”, and mine to praise and defend the madness of such characters and exuberance in literature- I can only hope that one day I will arrive at a place where I am so “obliged to sing my own praises” as impressively and eloquently as my hero of La Mancha.

Friday, November 7, 2008

My "Touchstone" Moment

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

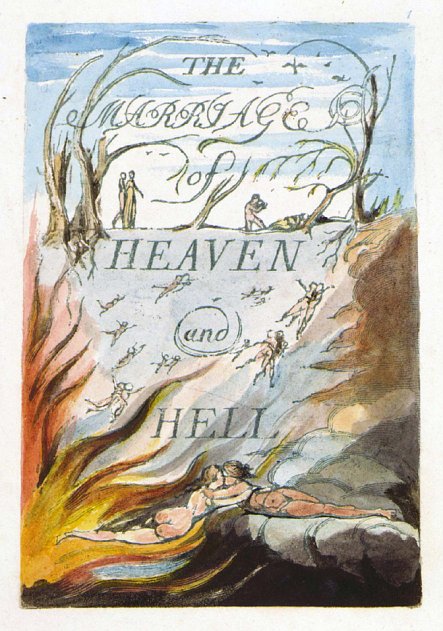

"The Marriage of Heaven and Hell"

Saturday, November 1, 2008

Reason vs. Passion

Reason and Passion

And the priestess spoke again and said: 'Speak to us of Reason and Passion.'

Wednesday, October 22, 2008

Nabokov: "Quit Laughing at Don Quixote!"

Mad-man of La Mancha

"The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom"

The abundance of William Blake paintings out there really surprised me, first because i've always heard of William Blake in the context of poetry and had no idea he was a painter/engraver as well and second because these painting are OUT THERE, exhuberant, OVER-THE-TOP, wooo wooooooooo............

((More on Blake to come))

Hymn to Intellectual Beauty

Ode on a Grecian Urn

For ever warm and still to be enjoy'd,

For ever panting, and for ever young;

All breathing human passion far above,

That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy'd,

A burning forehead, and a parching tongue.

Saturday, October 11, 2008

Rhapsody to Rilke

"As the bees bring in the honey, so do we fetch the sweetest out of everythingEffectively, the poet builds god, he and god are one. Anagogic may be the only one of the 5 symbolic phases i'm clear on, thanks to the Rilke allusion.

and build Him. With the trivial, even with the insignificant (if it but happens

out of love) we make a start...with everything we do alone...we begin him"

(Rilke)

Wednesday, October 8, 2008

Polemics, Apologetics

Curiously enough (leave it to the genius of wikipedia- one thing leads to another, link after link of synchronization), the definition for polemic included it's antonym: Apologia. As in Apologetics. Apologists argue for, rather than against, those touchy theories. Apologia is Frye= polemics. Sidney/ Shelley= apologetics. Anyways, i thought it was quite interesting that Frye and Sidney are by definition, opposites, both in style and in school of thought, since that was the initial impression I got in reading and comparing their works.

Myth of the Declining Ages

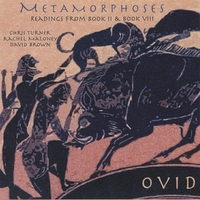

"I want to speak about bodies changed into new forms. You, gods, since you

are the ones who alter these, and all other things, inspire my attempt, and spin

out a continuous thread of words, from the world's first origins to my own

time."This is, essentially, the idea that all poems are made out of other poems; all stories are a retelling; all literature is displaced myth: this is the assertion at the heart of Frye's theories on literary criticism. And lo and behold, it's Ovid! Amazing....

Check out the Myth of the declining ages, which recalls another part of our class discussion today, that of scripture and the religious interpretation of myth. Frye says that all literature is an extension of myth and you will see outlined in the myth of the declining ages the story of the fall of the man in the Bible (followed by Jupiter attempting to destroy the world with a flood. Biblical?)

And that's just the beginning...

Friday, October 3, 2008

Apology for Criticism

However, I came across a passage today in Frye that struck me for it's convincing argument for criticism- so convincing that I had sort one of those lightbulb moments where it all came together: This is why criticism is so important!

It happened on Page 87 in the theory of symbols essay. Citing the example of the Bible as the inevitability of a sacred book and commentary on it's contents, Frye asserts that "when a poetic structure attains a certain degree of concentration or social recognition, the amount of commentary (read: criticism) that it will attain is infinite" (Frye 88). The analogies that follow to explain the inevitability and need for the critic, such as that of the scientist who is able to make theories about phenomenas in the universe that he cannot see or count, gave me the insight i needed to grasp this idea: "there is no occasion for wondering... how one small poet's head can carry the amount of wit, wisdom, instruction, and significance that Shakespeare and Dante have given the world" (Frye 88). And just like that I can't debate the relevance of criticism any more. As the poet's words, however beautiful they may be, are open to infinite interpretations and reactions, there is a case for criticism.

A Visionary Critic

Wow. In reading the briefest of brief summaries of the life of William Blake I can already say that I get it. I understand Sexson's insistence on the importance of this man to literary criticism. And that is just from the summary. I've yet to read this man's work (which goes beyond just poetry) and see what everybody's talking about. Additionally, a while back when I first wiki-ed Northrop Frye for information on "Anatomy of Criticism", I was linked to his biography (Frye) in which I discovered, in the first few sentences of the wiki-bio, that William Blake was one of Frye's primary influences. In fact, it was "The insights gained from his study of Blake" that "set Frye on his critical path,and shaped his contributions to literary criticism and theory" (wikipedia, Northrop Frye). Statements such as this suggest that in our thorough studies of the theories of Northrop Frye, we have been, effectively, studying William Blake all along. "Anatomy of Criticism" was inspired by Frye's works on Blake.

Blake's philosophy is in the vein of our favorite romantics: imagination above reason, exhuberance: "His poetic and artistic work is characterized by a unique commitment to imagination as opposed to reason, and the visionary, almost terrifying, and sometimes grotesque nature of his subject matter" (William Blake- poets.org) And I would go further as to say not only by exhuberant ideas, but also an exhuberant manner of presentation of these ideas: in "illuminated manunscripts"- text, engravings, illustrations all intertwined.

"I must create a system or be enslaved by another man's" said Blake. Isn't this the cyclical thought behind the chapters in Frye we are studying now?

I've read a bit about Blake as a poet and painter thus far, but i've yet to look into his role as a critic. Although I suppose that these roles are really one in the same.

Tautologically Speaking...

I think that literary criticism would be one such idea. Actually, when I was first getting into the theory of symbols, my initial thought was "Is this how you have to write in order to express a theory without a trace of tautology?" and, if so, what hope is there for the rest of us!

That was initially, as I read further I started to make note of some sentences that, within some very dense and meticulous passages, sound right repetitive... in Frye. For example, in "Literal and descriptive phases: symbol as motif and sign", I was a little stunned after reading this one:

"Poetic images do not state or point to anything, but, by pointing to eachother, they suggest or inform the mood that informs the poem" (Frye 81). Now, that sounds circular to me. But I'm sure a critic like Frye would never implore such a pathetic principle in his work.

Am I not getting the right idea of what Tautology is?

A wiki-search for the definition asks me to be a little more specific.... do I want to define tautology in regards to rhetoric or tautology in logic. I assume for our classes purposes, the rhetorical version. But just out of curiosity, what's the difference?

Tautology (rhetoric) is what we were making fun of Sarah Palin for in class- that is, the unecessary repetition of an idea; using different words to say the same thing twice. People who implore this rhetoric technique end up sounding either a)confusing, b) like children or c) like idiots. Rhetorical tautology can be logical if the sentence illustrates a truth, but it will usually be a completely useless assertions (wiki ex: "If you can't find it, you're not looking in the right place). Basically tautoloy in rhetoric is always going to be useless, senseless, or unecessary.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tautology

As for tautology in logic- tautology that actually points to the truth and gets you somewhere.... that's a concept for the mathmeticians.

Wednesday, October 1, 2008

Music, Sweet Music

But in the most recent reading of Frye, in between those "overboard" passages, I did happen upon some analogies that gave me some clarity. Fresh off of this newfound "understanding" of Frye (a vague understanding, but thats better than my previous state), I was very grateful for the "lightbulb" moments assignment we recieved in class today. In the last couple of days I've had a few to contribute!

It started for me in the description of the formal phase in the theory of symbols. (The formal phase which coincides with the New Critic's school of thought, which I'm to adopt for the final project), wherein Frye suggests the analogy of music as a way of understanding the roles of form and imagery in text. "The average audience at a symphony knows very little about sonata form, and misses practically all the subtleties detected by an analysis of the score; yet those subtleties are really there, and as the audience can hear everything that is being played, it gets them all as a part of a linear experience; the awareness is less concious, but not less real. The same is true of the response to the imagery of a highly poetic drama."

As with Walter Pater ("All the arts aspire to music") and Rilke ("Language where all language ends"), nothing proves more infallible an analogy than that of Music.

Comparing Criticisms

Tuesday, September 30, 2008

That is like, SOO American!

theories influenced some of the most highly exalted authors in history (his Scienza Nuovo - The New Science was used by James Joyce to write Finnegan's Wake, and his ideas were largely implored by Samuel Taylor Coleridge), I'm asking myself how it is that I haven't heard the name before in my 3 years of university. Well, a further inquiry into some of the ideas behind Scienza Nuovo revealed Vico to be as relevant to a class on literary criticism as Frye! It was his role as rhetorician, however, that i really wanted to delve into as it is was the most pertinent to our discussion that day- on the decline of literary expression and our modern day, pathetic, rhetorical fads. If you'll remember Sexson's reference to Vico in class, this was the guy who said "you cannot seperate poetry and history". He says that "the entire universe is in a constant state of decline since the beginning". The beginning, that is, when the gods were in charge and the world was in a pure state, which then fell- but not too drastically- to the heroes, and finally to men. Divine->Heroic-> Human. Vico marks each of these ages by the Trope or figurative language utilized in each. From the divine, biblical rhetoric of the gods to the "high filutant" (filutant, i'm assuming, to mean fanatical, excessive?) language of the epic heroes, to the language of men, the language of commerce, and now... Us. We are in a state of declination beyond lowly,mercantile language. We've digressed to the current age of jibberish...the language of "like, ___" "like, ___" "uhhhh" "i dunno".... "DUDE!" "Awesome" "sweeeeetnesss". This discussion in class sparked my attention because i've had a heightened awareness of these faddy discursive additives since i've come back to America 2 months ago (I'd like to add "Sooooo" to that list, it seems to be the way to begin any anecdote "Soooo, I was like, looking up Giambattista Vico on Wikipedia...."). After a year of speaking mostly spanish, and hardly any american interaction, I felt bombarded by this jargon when i got back, and I still am very aware of how awful it sounds now, though guilty of utilizing it myself. Every language has its coloquial, sort of dumbed-down phraseology. And this day in age it has become a language of chaos. It's jibberish! Vico said that language was like a "power-house of customs", a phenomena that reflects the beliefs, knowledge, abilities of it's people. Language and rhetoric reflect the transition from one stage to the next: from the divine, to the heroic, to the human. This is only one aspect of the theory being proposed by Vico in Scienza Nuovo. But since his time (late 17th early 18th century) we've definitely reached a more primitive state, in my opinion, rhetorically speaking.

theories influenced some of the most highly exalted authors in history (his Scienza Nuovo - The New Science was used by James Joyce to write Finnegan's Wake, and his ideas were largely implored by Samuel Taylor Coleridge), I'm asking myself how it is that I haven't heard the name before in my 3 years of university. Well, a further inquiry into some of the ideas behind Scienza Nuovo revealed Vico to be as relevant to a class on literary criticism as Frye! It was his role as rhetorician, however, that i really wanted to delve into as it is was the most pertinent to our discussion that day- on the decline of literary expression and our modern day, pathetic, rhetorical fads. If you'll remember Sexson's reference to Vico in class, this was the guy who said "you cannot seperate poetry and history". He says that "the entire universe is in a constant state of decline since the beginning". The beginning, that is, when the gods were in charge and the world was in a pure state, which then fell- but not too drastically- to the heroes, and finally to men. Divine->Heroic-> Human. Vico marks each of these ages by the Trope or figurative language utilized in each. From the divine, biblical rhetoric of the gods to the "high filutant" (filutant, i'm assuming, to mean fanatical, excessive?) language of the epic heroes, to the language of men, the language of commerce, and now... Us. We are in a state of declination beyond lowly,mercantile language. We've digressed to the current age of jibberish...the language of "like, ___" "like, ___" "uhhhh" "i dunno".... "DUDE!" "Awesome" "sweeeeetnesss". This discussion in class sparked my attention because i've had a heightened awareness of these faddy discursive additives since i've come back to America 2 months ago (I'd like to add "Sooooo" to that list, it seems to be the way to begin any anecdote "Soooo, I was like, looking up Giambattista Vico on Wikipedia...."). After a year of speaking mostly spanish, and hardly any american interaction, I felt bombarded by this jargon when i got back, and I still am very aware of how awful it sounds now, though guilty of utilizing it myself. Every language has its coloquial, sort of dumbed-down phraseology. And this day in age it has become a language of chaos. It's jibberish! Vico said that language was like a "power-house of customs", a phenomena that reflects the beliefs, knowledge, abilities of it's people. Language and rhetoric reflect the transition from one stage to the next: from the divine, to the heroic, to the human. This is only one aspect of the theory being proposed by Vico in Scienza Nuovo. But since his time (late 17th early 18th century) we've definitely reached a more primitive state, in my opinion, rhetorically speaking.