Even with an awareness of what was revealed in our class discussions about the end of Don Quixote, I still couldn't imagine our knight renouncing his life's quest. Even through the chapter where he is defeated by the knight of the white moon, i still didn't expect Don Quixote to submit to his orders and return to his village. Not very Quixotic! But I knew, on page 893, that our hero was lost, at this moment: "You sound very philisophical, Sancho... and you speak very wisely". What?!!? Did he just call Sancho Panza wise? That's when I knew that my hero was lost, and oh what a loss! Starting in chapter 66, just after his encounter with the knight of the white moon, this novel plummeted from hightly comedic to utterly tragic... all in the span of a few chapters, until his death. Even despite our revealing class discussions I did not expect Don Quixote to really renounce kniight errantry or to die, but its true, the end result is both. In chapter 66 there is still hope, because when he speaks of going into seclusion- his year sabatical from knight errantry- he says to Sancho "in that seclusion we shall sgather new strength to return to the practice of arms, which will never be forgotten by me" (894). But by the last chapter he has worsened to the point of cursing the "practice of arms" forever ("now all the profane histories of knight errantry have become hateful to me... I despise them) and, most tragic to me, saying they were a waste of his life. That is a painful statement. Almost 900 pages of thrill, adventure, passion- all a waste? That, to me, was the most tragic part of our hero's demise. When he says (p. 935) "My judgement is restored, free and clear of the dark shadows of ignorance imposed on it by my grievous and constant reading of detestable books of chivalry. I now recognize their absurdities and deceptions, and my sole regret is that this realization has come so late it does not leave me time to compensate by reading other books that can be a light to the soul". Other books? Is this my same Don Quixote? No it's not. He has lost his honor and self-dignity. No longer the "knight errant, daring and brave", he has transformed into an "ordinary gentleman" (NOOOO!) lacking the confidence, lacking those dignified self-introductions I loved so much! He actually asks Sancho to respond for him, doubting his own judgment and competency. The end of Don Quixote had me in tears, for the loss of a hero. I feel as disenchanted as Dulcinea, whom he sought throughout the entire book to no end.

Even with an awareness of what was revealed in our class discussions about the end of Don Quixote, I still couldn't imagine our knight renouncing his life's quest. Even through the chapter where he is defeated by the knight of the white moon, i still didn't expect Don Quixote to submit to his orders and return to his village. Not very Quixotic! But I knew, on page 893, that our hero was lost, at this moment: "You sound very philisophical, Sancho... and you speak very wisely". What?!!? Did he just call Sancho Panza wise? That's when I knew that my hero was lost, and oh what a loss! Starting in chapter 66, just after his encounter with the knight of the white moon, this novel plummeted from hightly comedic to utterly tragic... all in the span of a few chapters, until his death. Even despite our revealing class discussions I did not expect Don Quixote to really renounce kniight errantry or to die, but its true, the end result is both. In chapter 66 there is still hope, because when he speaks of going into seclusion- his year sabatical from knight errantry- he says to Sancho "in that seclusion we shall sgather new strength to return to the practice of arms, which will never be forgotten by me" (894). But by the last chapter he has worsened to the point of cursing the "practice of arms" forever ("now all the profane histories of knight errantry have become hateful to me... I despise them) and, most tragic to me, saying they were a waste of his life. That is a painful statement. Almost 900 pages of thrill, adventure, passion- all a waste? That, to me, was the most tragic part of our hero's demise. When he says (p. 935) "My judgement is restored, free and clear of the dark shadows of ignorance imposed on it by my grievous and constant reading of detestable books of chivalry. I now recognize their absurdities and deceptions, and my sole regret is that this realization has come so late it does not leave me time to compensate by reading other books that can be a light to the soul". Other books? Is this my same Don Quixote? No it's not. He has lost his honor and self-dignity. No longer the "knight errant, daring and brave", he has transformed into an "ordinary gentleman" (NOOOO!) lacking the confidence, lacking those dignified self-introductions I loved so much! He actually asks Sancho to respond for him, doubting his own judgment and competency. The end of Don Quixote had me in tears, for the loss of a hero. I feel as disenchanted as Dulcinea, whom he sought throughout the entire book to no end.Thursday, November 27, 2008

At The End of Don Quixote: the book and the man

Even with an awareness of what was revealed in our class discussions about the end of Don Quixote, I still couldn't imagine our knight renouncing his life's quest. Even through the chapter where he is defeated by the knight of the white moon, i still didn't expect Don Quixote to submit to his orders and return to his village. Not very Quixotic! But I knew, on page 893, that our hero was lost, at this moment: "You sound very philisophical, Sancho... and you speak very wisely". What?!!? Did he just call Sancho Panza wise? That's when I knew that my hero was lost, and oh what a loss! Starting in chapter 66, just after his encounter with the knight of the white moon, this novel plummeted from hightly comedic to utterly tragic... all in the span of a few chapters, until his death. Even despite our revealing class discussions I did not expect Don Quixote to really renounce kniight errantry or to die, but its true, the end result is both. In chapter 66 there is still hope, because when he speaks of going into seclusion- his year sabatical from knight errantry- he says to Sancho "in that seclusion we shall sgather new strength to return to the practice of arms, which will never be forgotten by me" (894). But by the last chapter he has worsened to the point of cursing the "practice of arms" forever ("now all the profane histories of knight errantry have become hateful to me... I despise them) and, most tragic to me, saying they were a waste of his life. That is a painful statement. Almost 900 pages of thrill, adventure, passion- all a waste? That, to me, was the most tragic part of our hero's demise. When he says (p. 935) "My judgement is restored, free and clear of the dark shadows of ignorance imposed on it by my grievous and constant reading of detestable books of chivalry. I now recognize their absurdities and deceptions, and my sole regret is that this realization has come so late it does not leave me time to compensate by reading other books that can be a light to the soul". Other books? Is this my same Don Quixote? No it's not. He has lost his honor and self-dignity. No longer the "knight errant, daring and brave", he has transformed into an "ordinary gentleman" (NOOOO!) lacking the confidence, lacking those dignified self-introductions I loved so much! He actually asks Sancho to respond for him, doubting his own judgment and competency. The end of Don Quixote had me in tears, for the loss of a hero. I feel as disenchanted as Dulcinea, whom he sought throughout the entire book to no end.

Even with an awareness of what was revealed in our class discussions about the end of Don Quixote, I still couldn't imagine our knight renouncing his life's quest. Even through the chapter where he is defeated by the knight of the white moon, i still didn't expect Don Quixote to submit to his orders and return to his village. Not very Quixotic! But I knew, on page 893, that our hero was lost, at this moment: "You sound very philisophical, Sancho... and you speak very wisely". What?!!? Did he just call Sancho Panza wise? That's when I knew that my hero was lost, and oh what a loss! Starting in chapter 66, just after his encounter with the knight of the white moon, this novel plummeted from hightly comedic to utterly tragic... all in the span of a few chapters, until his death. Even despite our revealing class discussions I did not expect Don Quixote to really renounce kniight errantry or to die, but its true, the end result is both. In chapter 66 there is still hope, because when he speaks of going into seclusion- his year sabatical from knight errantry- he says to Sancho "in that seclusion we shall sgather new strength to return to the practice of arms, which will never be forgotten by me" (894). But by the last chapter he has worsened to the point of cursing the "practice of arms" forever ("now all the profane histories of knight errantry have become hateful to me... I despise them) and, most tragic to me, saying they were a waste of his life. That is a painful statement. Almost 900 pages of thrill, adventure, passion- all a waste? That, to me, was the most tragic part of our hero's demise. When he says (p. 935) "My judgement is restored, free and clear of the dark shadows of ignorance imposed on it by my grievous and constant reading of detestable books of chivalry. I now recognize their absurdities and deceptions, and my sole regret is that this realization has come so late it does not leave me time to compensate by reading other books that can be a light to the soul". Other books? Is this my same Don Quixote? No it's not. He has lost his honor and self-dignity. No longer the "knight errant, daring and brave", he has transformed into an "ordinary gentleman" (NOOOO!) lacking the confidence, lacking those dignified self-introductions I loved so much! He actually asks Sancho to respond for him, doubting his own judgment and competency. The end of Don Quixote had me in tears, for the loss of a hero. I feel as disenchanted as Dulcinea, whom he sought throughout the entire book to no end.In Memory of WB Yeats

I looked this poem up on google because Sexson cited the beautiful last lines after my presentation, reminding us that poetry is meant to praise, and that a defense of poetry is, effectively, it's praise. Here is the poem in its entireity.

This is the poet WH Auden who wrotet "In Memory of WB Yeats". Not surprisingly, he was greatly influenced by William Blake.

http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/15544

http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/15544

For some reason, when i searched for this poem i was bombarded by website from church groups. Its been used in an large amount of sermons.

More term paper support via Don Quijote

I would like to include a few more parts from Don Quixote that take place in one of the episodes I used in my term paper, that is, "regarding what befell Don Quixote with a prudent knight of La Mancha" (Cervantes 550). That prudent knight being the man in the green coat. This episode is chock full of material that defends not only poetry, but specifically, english majors and student poets! Because, to reiterate, the man in the green coat is venting to Don Quixote about his frustrations with his son, who "isn't as good as he would like him to be" due to his choice of studies, which is Latin and Greek Languages. His father sees this as a complete waste of time, and is frustrated that instead of moving onto other areas of knowledge, he continues to read and debate books and poetry. Don Quixote advises him that although it is true that "poetry is less useful than pleasurable" (Cervantes 556). He echoes everything we've heard from subsequent defenders of poetry this semester, saying that "art does not surpass nature but perfects it; therefore, when nature is mixed with art, and art with nature, the result is a perfect poet" (557). And in his conclusion- and this is the big line for all us english majors- Don Quixote defends our field of study, praising the man's son for having "already successfully climbed the first essential step, which is languages, with them he will, on his own, mount to the summit of human letters, which are so admirable in a gentleman" (557)

Term paper posted

In Praise of Poetry: My Inspiration in Literature

"This purifying of wit-this enriching of memory, enabling of judgment, and enlarging of conceit-which commonly called learning, under what name soever it come forth, or to what immediate end soever it be directed, the final end is to lead and draw us to as high a perfection as our degenerate souls, made worse by their clayey lodging, can be capable of."

Sir Philip Sidney

To Inform. To take. To create. By means of my education I have come and will continue to come into my own. Learning has led me to an awareness of my own passion for poetry, and thus, passion for life: of what I need and where I need to go in my life. This quote from Sir Phillip Sidney’s “Defense of Poetry” succeeds in expressing expresses in words what, naturally, I could not, and so stood out from the entire essay to me, and this entire course, as a summary of what I’ve been mulling over in my mind for so long: the beauty of knowledge, education, information: the poetry of wisdom. It is through this journey of learning that I have and will continue to confront the best version of myself.

I would like to model that ideal version of myself on that ingenious hidalgo Don Quixote of La Mancha, a hero by my standards, and in a sense that is completely un-pared in all literature I’ve encountered. Senor Quixote begins his quest when he dedicates himself to the pursuits of knight errantry; he makes it his mission to imitate the language of his books. It takes an understanding and appreciation of literature (which I harbor in my heart as an English major) to consider this mission as one of utmost honor, and not in the least bit farce. In fact I envy our hero for boasting this as his life’s mission: to live himself into his books. Don Quixote speaks of himself and his adventures in the style of the books of chivalry that have ransacked his mind. Oh, that Don Quixote would ransack my mind and invoke me to speak in this high rhetoric so long ago lost! Even if everyone I encounter on my journey thinks me mad, that I would pay it no mind, like our hero. I have wistful notions of adopting Don Quixote’s mission and his rhetoric, but alas, I cannot even read his words out-loud and sound convincing, much less invent my own discourse. I suppose I fear those accusations of madness that the Knight of La Mancha handles so gracefully. That I would be so graceful, this Knight is my hero! The high-rhetoric and wit and wisdom via madness that Don Quixote possesses, his delightfully dignified manner of presenting himself: I envy the hidalgo for all these heroic qualities.

As different as I am from Don Quixote in some respects (those listed in the previous sentence, for instance), I feel smugly similar to him in others. We both have our books, of course (that is we share a dependence on literature). And we have something else, too.

I recall one of many episodes where the knight defends himself and his profession, in Chapter 13 of the First Part, after Don Quixote has met a group of goatherds on the road and is traveling with them to a funeral. One of the travelers they encounter en route to the burial begins to interrogate Don Quixote about his purpose in the land, to which he reiterates his usual elegant explanation of his mission as a knight errant. They immediately consider him mad, both for his exuberant undertaking and equally exuberant way of relating it. They continue to inquire, so as to gauge exactly how mad he is. Don Quixote speaks to them of great knights and soldiers of the past like King Arthur, and then audaciously praises theses knights as more valiant than priests and religious men, because they actively defend the morality that priests only speak about. “In this way we are ministers of God on earth, the arms by which His justice is put into effect on earth” (Cervantes 88). It’s an outrageous claim, I know, but I would defend the poets in the exact same way, including myself: the poets represent the divine in art. Further on in the book, Don Quixote gets another chance to explain lend his knightly wisdom and opinions to a stranger he meets on the road- this time a man in a green coat, with a son studying languages in university. The man in the green coat confesses that he is troubled by his son’s coursework, which he hardly considers to be an “area of knowledge” worth studying. Don Quixote does a better job than I can of defending his son’s choice of curriculum, as well as defining anagogy and praising the poet, explaining that the natural poet, “with that inclination granted to him by heaven, with no further study or artifice composes things that prove the truthfulness of the man who said: Est Dues in nobis” (Cervantes 557). God is in us.

Outrageous. Extravagant. Over-the-top. How could I compare myself to that ingenious knight of La Mancha? I suppose I aim to model myself off of this man just as he does those warriors in his beloved books of chivalry. And since the imaginative Don Quixote makes a far better symbol of poetry than he does a knight errant anyway, maybe it’s not that outrageous.

And so I declare that I am an English major, “the kind, as people say, who go to seek adventures” (Cervantes 553), and like my hero, I am willing to leave my home and comfort and “throw myself into the arms of Fortune so that she may carry me wherever she chooses” that I might “fulfill a good part of my desire” (Cervantes 553). While our desires may differ- his being “to revive a long-dead knight errantry”, and mine to praise and defend the madness of such characters and exuberance in literature- I can only hope that one day I will arrive at a place where I am so “obliged to sing my own praises” as impressively and eloquently as my hero of La Mancha.

"This purifying of wit-this enriching of memory, enabling of judgment, and enlarging of conceit-which commonly called learning, under what name soever it come forth, or to what immediate end soever it be directed, the final end is to lead and draw us to as high a perfection as our degenerate souls, made worse by their clayey lodging, can be capable of."

Sir Philip Sidney

To Inform. To take. To create. By means of my education I have come and will continue to come into my own. Learning has led me to an awareness of my own passion for poetry, and thus, passion for life: of what I need and where I need to go in my life. This quote from Sir Phillip Sidney’s “Defense of Poetry” succeeds in expressing expresses in words what, naturally, I could not, and so stood out from the entire essay to me, and this entire course, as a summary of what I’ve been mulling over in my mind for so long: the beauty of knowledge, education, information: the poetry of wisdom. It is through this journey of learning that I have and will continue to confront the best version of myself.

I would like to model that ideal version of myself on that ingenious hidalgo Don Quixote of La Mancha, a hero by my standards, and in a sense that is completely un-pared in all literature I’ve encountered. Senor Quixote begins his quest when he dedicates himself to the pursuits of knight errantry; he makes it his mission to imitate the language of his books. It takes an understanding and appreciation of literature (which I harbor in my heart as an English major) to consider this mission as one of utmost honor, and not in the least bit farce. In fact I envy our hero for boasting this as his life’s mission: to live himself into his books. Don Quixote speaks of himself and his adventures in the style of the books of chivalry that have ransacked his mind. Oh, that Don Quixote would ransack my mind and invoke me to speak in this high rhetoric so long ago lost! Even if everyone I encounter on my journey thinks me mad, that I would pay it no mind, like our hero. I have wistful notions of adopting Don Quixote’s mission and his rhetoric, but alas, I cannot even read his words out-loud and sound convincing, much less invent my own discourse. I suppose I fear those accusations of madness that the Knight of La Mancha handles so gracefully. That I would be so graceful, this Knight is my hero! The high-rhetoric and wit and wisdom via madness that Don Quixote possesses, his delightfully dignified manner of presenting himself: I envy the hidalgo for all these heroic qualities.

As different as I am from Don Quixote in some respects (those listed in the previous sentence, for instance), I feel smugly similar to him in others. We both have our books, of course (that is we share a dependence on literature). And we have something else, too.

I recall one of many episodes where the knight defends himself and his profession, in Chapter 13 of the First Part, after Don Quixote has met a group of goatherds on the road and is traveling with them to a funeral. One of the travelers they encounter en route to the burial begins to interrogate Don Quixote about his purpose in the land, to which he reiterates his usual elegant explanation of his mission as a knight errant. They immediately consider him mad, both for his exuberant undertaking and equally exuberant way of relating it. They continue to inquire, so as to gauge exactly how mad he is. Don Quixote speaks to them of great knights and soldiers of the past like King Arthur, and then audaciously praises theses knights as more valiant than priests and religious men, because they actively defend the morality that priests only speak about. “In this way we are ministers of God on earth, the arms by which His justice is put into effect on earth” (Cervantes 88). It’s an outrageous claim, I know, but I would defend the poets in the exact same way, including myself: the poets represent the divine in art. Further on in the book, Don Quixote gets another chance to explain lend his knightly wisdom and opinions to a stranger he meets on the road- this time a man in a green coat, with a son studying languages in university. The man in the green coat confesses that he is troubled by his son’s coursework, which he hardly considers to be an “area of knowledge” worth studying. Don Quixote does a better job than I can of defending his son’s choice of curriculum, as well as defining anagogy and praising the poet, explaining that the natural poet, “with that inclination granted to him by heaven, with no further study or artifice composes things that prove the truthfulness of the man who said: Est Dues in nobis” (Cervantes 557). God is in us.

Outrageous. Extravagant. Over-the-top. How could I compare myself to that ingenious knight of La Mancha? I suppose I aim to model myself off of this man just as he does those warriors in his beloved books of chivalry. And since the imaginative Don Quixote makes a far better symbol of poetry than he does a knight errant anyway, maybe it’s not that outrageous.

And so I declare that I am an English major, “the kind, as people say, who go to seek adventures” (Cervantes 553), and like my hero, I am willing to leave my home and comfort and “throw myself into the arms of Fortune so that she may carry me wherever she chooses” that I might “fulfill a good part of my desire” (Cervantes 553). While our desires may differ- his being “to revive a long-dead knight errantry”, and mine to praise and defend the madness of such characters and exuberance in literature- I can only hope that one day I will arrive at a place where I am so “obliged to sing my own praises” as impressively and eloquently as my hero of La Mancha.

Friday, November 7, 2008

My "Touchstone" Moment

Since I became a declared "English Major", I've reached countless epiphanies via "touchstone" passages that we discussed in class pertaining to matthew arnold's essay. But the first work that ever had a memorable and lasting literary impact on me was Rilke's "Letters to a Young Poet", that I talked about in a previous blog. However I'm unable to single out just one touchstone moment from the letters, they're all too important and relevant! here are the ones that I hold the most dear:

"Things are not at all so comprehensible and expressible as one would mostly have us believe; most events are inexpressible, taking place in a realm which no word has ever entered, and more inexpressible than all else are works of art, mysterious existences, the life of which, while ours passes away, endures" (chapter 1)

"Everything is gestation and then birthing. To let each impression and each embryo of a feeling come to completion, entirely in itself, in the dark, in the unsayable, the unconscious, beyond the reach of one's own understanding, and with deep humility and patience to wait for the hour when a new clarity is born: this alone is what it means to live as an artist: in understanding as in creating." (ch. 3)

"You are so young, so before all beginning, and I want to beg you, as much as I can...to be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms and like books that are written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer." (ch. 4)

"Only be attentive to that which rises up in you and set it above everything that you observe about you. What goes on in your innermost being is worthy of your whole love." (ch. 6)

"Were it possible for us to see further than our knowledge reaches, perhaps we would endure our sadnesses with greater confidence than our joys. For they are moments when something new has entered into us, something unknown." (ch 8)

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

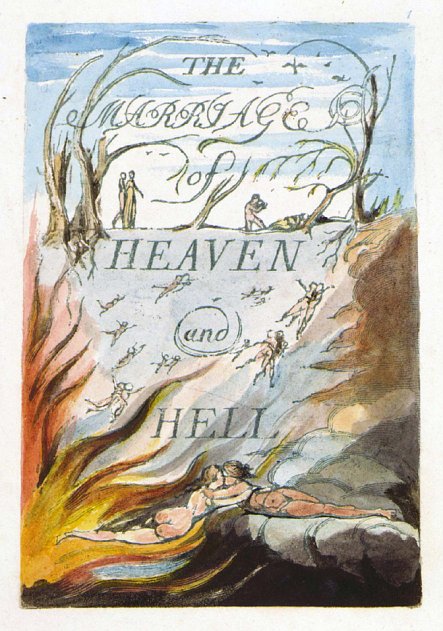

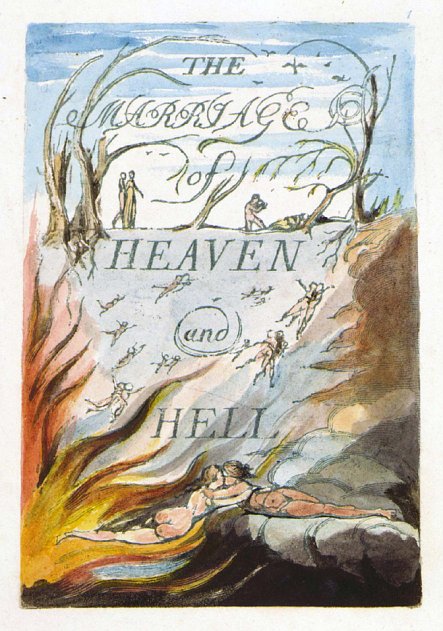

"The Marriage of Heaven and Hell"

Keeping with the theme of Reason vs. Passion, I'd like to now apply it to the ideology of my critic, William Blake, who wrote an entire epic poem addressing this battle.

"The Marriage of Heaven and Hell" tells of an epic descent into hell in the vein of Dante's "Inferno" and Milton's "Paradise Lost". However, Blake's Heaven and Hell in this book are completely reversed from Dante's or Milton's, where Hell is depicted as a burning torture chamber and Heaven a perfect paradise. Blake's Heaven is, effectively, the terrain of the reality principle, and Hell a land where passion reigns. Blake's obvious defense of Hell is testimony to his philosophies as a poet and critic: that all of life should be drawn from imagination, energy, and passion.

Saturday, November 1, 2008

Reason vs. Passion

Our discussions lately in class of Negative Capability brought to mind a poem that meant a lot to me by Kahlil Gibran. It was after reading this poem some years ago that I first acknowledged the existence of that internal struggle between reason and passion that we experience as humans. Before I think I understood it religiously, as a conflict between God's will and Satan's within us, or simpler put, Good vs. Evil. And this poem really opened my eyes to the true struggle, and beautifully depicted I might add. There are almost thirty poems included in this book, "The Prophet", each addressing a different trial of being human, but this was without question my favorite....

Reason and Passion

And the priestess spoke again and said: 'Speak to us of Reason and Passion.'

And he answered saying:

Your soul is oftentimes a battlefield, upon which your reason and your judgment wage war against passion and your appetite.

Would that I could be the peacemaker in your soul, that I might turn the discord and the rivalry of your elements into oneness and melody.

But how shall I, unless you yourselves be also the peacemakers, nay, the lovers of all your elements?

Your reason and your passion are the rudder and the sails of your seafaring soul.

If either your sails or our rudder be broken, you can but toss and drift, or else be held at a standstill in mid-seas.

For reason, ruling alone, is a force confining; and passion, unattended, is a flame that burns to its own destruction.

Therefore let your soul exalt your reason to the height of passion; that it may sing;

And let it direct your passion with reason, that your passion may live through its own daily resurrection, and like the phoenix rise above its own ashes.

I would have you consider your judgment and your appetite even as you would two loved guests in your house.

Surely you would not honour one guest above the other; for he who is more mindful of one loses the love and the faith of both.

Among the hills, when you sit in the cool shade of the white poplars, sharing the peace and serenity of distant fields and meadows - then let your heart say in silence, 'God rests in reason.'

And when the storm comes, and the mighty wind shakes the forest, and thunder and lightning proclaim the majesty of the sky, - then let your heart say in awe, 'God moves in passion.'

And since you are a breath In God's sphere, and a leaf in God's forest, you too should rest in reason and move in passion.

-Kahlil Gibran, "The Prophet"

This is a theme we encounter a lot in literature. As we discussed in class, there is a war between the pleasure principle and the reality principle, what we should do and what we want to do. Depending on what we obide by, we fall into two categories. There are the Don Quijotes, who adhere to the pleasure principle and our desires, who see the world but see something else, too. And then there are the Sancho Panzas, the realists, who adhere to the reality principle.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)