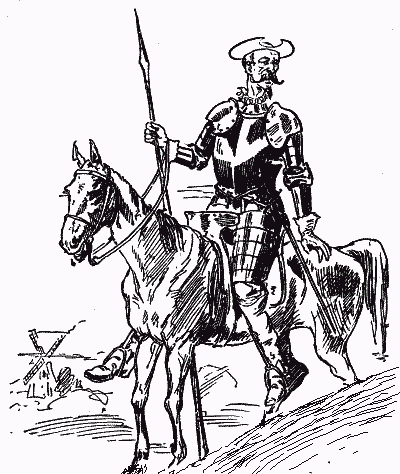

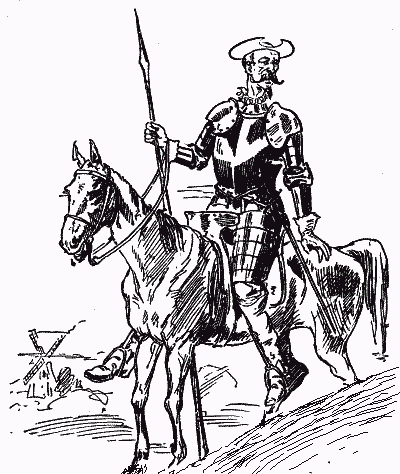

Nabokov agrees with Aristotle's assertions in 'Poetics': "Tragedy wears better than comedy" (Nabokov 13). We see in the protagonists of our novel the embodiment of both: Sancho, whose prescense offers comedic relief, and "The Knight of the Mournful Countenance": blatantly the embodiment of tradgedy itself. With his face sunken and withered, and

his under-fed body, he

looks like a tradgedy. His armor is worn and moldy, his horse is less than valiant looking.

But his behavior works in complete opposition to pathetic appearance.

He speaks exquisitlely, is courteous

and respectful, and carries himself with utmost confidence. Nabokov spells it out and I agree; Don Quixote is "a hero in the truest sense of the word" (Nabokov 16).

We have the confident, courteous, and chivalric Don Quixote, but he exists in conjuntion with the madman Don Quijote. His elegance is subject at any given moment to fits of utter insanity. In his portrait of Don Quixote, Nabokov provides a complete analysis of "that basic madness of his". Before he went mad, he was a simple and kind country gentleman... a completely different character from his complex transformation into Don Quixote, who replaces Senor Alonso when he vows to commit his life to the pursuits of knight errantry. Later he renounces this commitment,cursing it as the cause of his ruination, and completeing the tradgedy of the novel.

Most readers, myself included, might read Nabokov's lectures and doubt his claim that Don Quijote is a tragic figure and the novel is a tradgedy. I was scanning for sarcasm as I went through them, wondering if Nabokov was seriously insisting that there is nothing funny about the plight of Don Quijote (this, again, coming from a girl who was laughing out loud by herself in her bedroom as she followed each outrageous episode of the knight and his squire). After speaking with Dr. Sexson yesterday, though, and re-reading the lectures as well, I am starting to consider Nabokov's point. From the day he devotes himself to "the colorful calling of knight errantry... with all it's brilliant visions, emotions and acts", he is ridiculed, taken advantage of, and mocked... and that's putting it lightly. All that befalls him henceforth is hurtful. Furthermore, he is viewed by those around him as insane: this is a highly debateable topic. Is our hero really insane? Or is he a man on a mission with a wild imagination who is constantly the victim of wicked trickery? His world, the world of the novel, is an ambigious world of reality and illusion. One can never know.

Nabokov recalls this conversation between Don Quixote and his squire, which, when as I consider it again outside of the adventure of the novel, allows me to understand his tragedy.

"How is it possible for you to have accompanied me all this time without coming to perceive that all the things that have to do with knight-errantry appear to be mad, foolish, and fantastic... Not that they are so in reality: it is simply that there are always a lot of enchanters going about among us, changing things and giving them a deceitful appearance, directing them as suits their fancy, depending upon whether they wish to favor or destroy us". (I wonder if Sancho even understands this nobel speech!) And actually now, re-reading that statement as i write it down, i feel tears brimming in my eyes because that is Don Quixote's world, and really it is our world too. That is the tragic sense of life. That there is always evil and people inspired by evil that are working to bring us down. "Enchanters among us" with deceitful intentions. I thought the tragedy of Don Quixote arose at the end of the novel when he renounces knight errantry, but it actually comes into play from the minute he commits himself to it. Sancho is there for comedic relief. But Don Quixote is alone in his world and troubled by his perceptions of the world around him which he sees as his duty to defend. It is outrageously honorable for him to accept this task in the first place, the task of weighing reality and illusion and defending madness and himself against the immoral attacks of the evil he encounters. And Don Quixote is a literary hero for attempting it, but in the end, even he cannot complete it. That is the great tragedy of this novel.

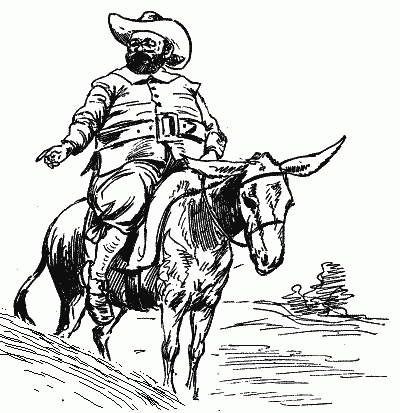

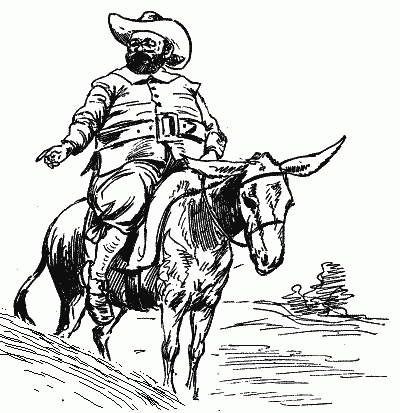

As for the role of Sancho "Pig Belly" Panza, we can't consider him a complete fool or simpleton- the things that come out of his mouth are far too clever at times to diminish him with those names- but he is certainly outshined by his master and foil, Don Quixote. Where as Sancho Panza is "a product of generalization" (Nabokov 20), Don Quixote is the emblem of individuality. In Nabokov's opinion his most human trait is his unfailing love and devotion to his master. He recalls a speech of Sancho's in the novel where he puts my exact thoughts into words about our hero: "Why, damn me, how your grace does manage to say everything here just the way it should be said, and how well you work that Knight of the Mournful Countenance into the signature!" (Nabokov 20). That is exactly what I think as I marvel over the impressive rhetoric and wisdom of the man of la mancha. In analyzing the two main characters of the great novel, Nabokov sets up his main point (which has been stressed and mulled over in LitCrit this semester) that they represent two ways of looking at the world: "The explication of critical attitudes toward the two heroes lies, I suspect, in the fact that all readers can be separated into Don Quixotes and Sancho Panzas" (Nabokov 24).

Nabokov gives brief attention later to the structural devices of the novel, but he only points them out and goes no further. In his opinion, there is nothing to praise regarding the technique of the novel, which would be nothing if it weren't for the character it takes it's title from. "Don Quixote has been called the greatest novel ever written. This, of course, is nonsense." (GASP!) "...but it's hero, whose personality is a stroke of genius on the part of Cervantes, looms so wonderfully above the skyline of literature... that the book lives and will live through the sheer vitality that Cervantes has injected into the main character of a very patchy haphazard tale, which is saved from falling apart only by its creator's wonderful artisitic intuition that has his Don Quixote go into action at the right moments of the story" (Nabokov 29). Now, Nabokov has a way of turning your mind over. Every point he makes about the novel is brilliant and true, and not at all what anyone would initially consider upon reading it. But this novel is nothing without it's hero, think about it, if Cervantes had wrote any less of a madman into the lead role, would anybody be interested in this jolty ensemble of outrageous episodes. Don Quixote is that dynamic of a character, not only does he pull the novel together, but he has allowed it to endure as "the greatest novel of all time" in many reader's eyes. And Nabokov's goal in these lectures is not to disillusion readers as far as the integrity of this novel, but really to give credit where credit is due, I think. Cervantes isn't the greatest writer of all time, he was a struggling playright who barely knew fame until he created Don Quixote. He didn't write the best novel of all time, but perhaps the best character. Don Quixote of La Mancha: "A hero in the truest sense of the word".